Examining the mythology and folklore surrounding the story of Ned Kelly

This essay begins to explore the influence of Australian stock characters and archetypes on Western popular culture by examining the mythology and folklore that encompasses the story of Ned Kelly.

Ever since Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly emerged from colonial obscurity in 1878, his story has continued to fascinate. Whether historical, imaginative, or a combination of both, Ned has maintained public interest and fired imaginations, much to the chagrin of those uncritical of the established order [Jones, 2002, p.103]. His historical narrative continues to grow as new evidence is unearthed. And, with the mystery surrounding Ned’s missing skull and the Gang’s declaration of independence for North East Victoria [Phillips, 2003], his final chapter is yet to be written.

From the rebellious spirit through to the iconic imagery of his armour, Ned Kelly’s narrative has permeated many Australians’ artistic and cultural insight. The folklore surrounding Ned manifested through whispered tales, bush ballads, newspaper reports, and G.W. Hall’s The Book of Keli [1879], published while the Kelly Gang was still at large. The story continued to grow long after Ned’s demise. In 1906, Australian filmmakers produced the world’s first feature-length narrative, The Story Of The Kelly Gang. Based on actual occurrences but with added drama, the movie helped lay the foundations for a modern, uniquely Australian form of popular culture and set the hero’s journey for our central character in motion. This film and several other bushranger movies made Australia one of the most prolific film-producing countries during the 1910s [Aveyard, Moran, Vieth, 2005, p.32]. It did not take long, however, before the genre began to attract the interest of the New South Wales government, which soon moved to restrict production due to what it described as ‘moral concerns’. Unfortunately for the local industry, this prudish approach allowed the better-funded Hollywood studios to quickly manipulate the bushranger diegesis and transform the style into the earliest blockbuster westerns.

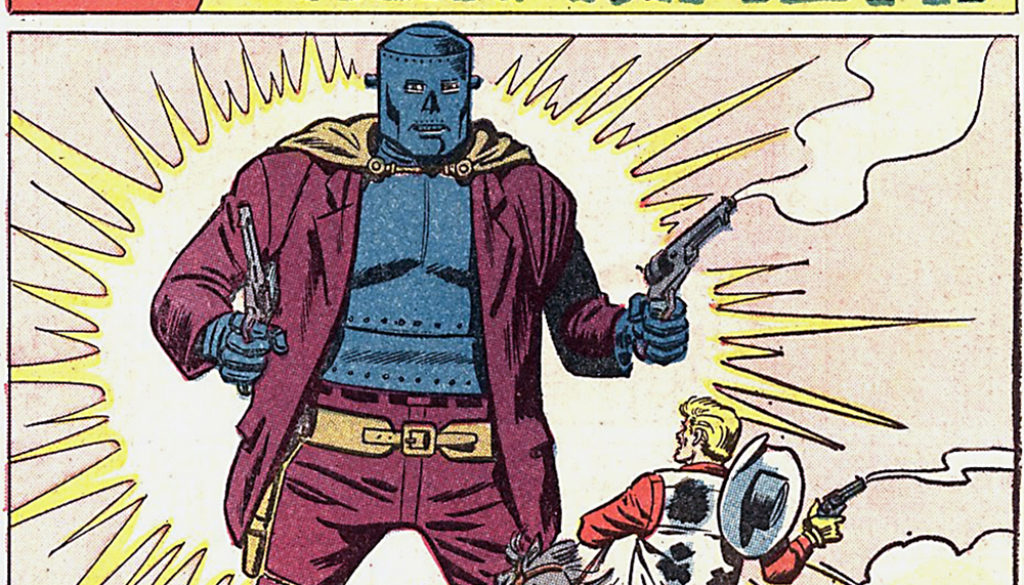

However, bushranger tales would continue to influence the Wild West narrative. Kelly’s legacy in folklore would reemerge in mid-20th century American western and crime comics, where artists like Lou Fine, Steve Ditko, and Jack Kirby launched their careers. These inventive representations would shape the origin stories of a number of modern day armoured characters including Iron Man and Dr Doom and manifest themselves into diverse reincarnations and reinterpretations, as can be seen in Monte Hale Western #58 [1951] [Figure 1]. It is now well accepted that during the 1960s ‘Silver age,’ publishers, including Marvel and DC, actively strip-mined names and concepts from appropriated, out of copyright, or discontinued ‘Golden age’ titles. They also altered exisiting storylines in an attempt to confuse the origins and then claimed the characters and plot lines as uniquely their own [Groth, 2011]. Even though vastly altered, many stories from the distant past still underpin the central themes of creative works in popular culture. For instance, the Coen brothers based their crime comedy-drama O Brother, Where Art Thou? [2000] on Homer’s The Odyssey [c. 8th century BC]. A more relevant pop culture example can be found in Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s creation of The Incredible Hulk #1 [1962] which was heavily influenced by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein [1818] and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde [1886] [Groth, 2011].

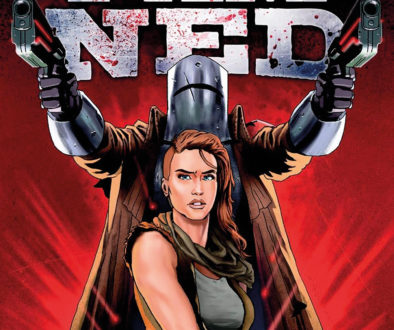

Regale a hearty folkloric tale at your local watering-hole concerning a bushman dressed in bullet proof armour and the elicited response should, at a minimum, convey an acknowledgement of Ned Kelly. His story, as expected, is better known around the Commonwealth, particularly New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. However, it is the United States of America who have embraced the anecdote of Ned’s armour to the detriment of his mythology. In many instances the armour itself has been bastardised, swapped out for generic bullet-proof suits [usually medieval in style] when it is convenient for the narrative as in The Cisco Kid #23 [1954] [Figure 2], or if the editor’s brief simply confounds the artist. The armour, which has been rerouted away from the story, now stands alone without context, lost in translation like a game of Chinese whispers.

Over the past century, Ned’s narrative has been delineated, parodied, and deconstructed. One of the most significant appropriations occurred soon after the Second World War when Sidney Nolan began his career defining Ned Kelly series. Nolan’s unique artistic approach which blended historical narrative with imaginative interpretation, would continue to influence artists up until this very day. The image of the Kelly Gang and their iconic armour has been reinterpreted by countless creatives in many styles and mediums through books, comics, movies, gaming, theatre, and art. The Kelly story and, specifically that of Ned, has become one of Australia’s seminal cultural memories and continues to serve as an inspiration both locally and internationally.

Nolan was motivated to create his Kelly series after reading J.J. Kenneally’s The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers [1929]. As successive conservative governments maintained a ban on films which glorified bushrangers, Kenneally’s publication was one of the the first books of note that was sympathetic to the Kellys. Previously, publications were dominated by anti-Kelly literature which portrayed Ned as a ruthless criminal and it was primarily oral tradition and folk songs that maintained his image as a popular hero. Ned’s narrative had also entered indigenous dreaming. The Yarralin people of the Northern Territory tell a story in which Captain Cook [a metaphor for the deleterious colonial relationships between white settlers and the aboriginal people] took Ned Kelly back to England where his throat was cut. The story continues, ‘They bury him. Leave him. Sun go down, little bit dark now, he left this world. BOOOOOMMMMM! Go longa top. This world shaking. All the white men been shaking. They all been frightened’ [Bird, 1992]. In the same way that Captain Cook came to represent the oppressive side of white settlement the author, Deborah Bird Rose, argues that the Kelly story has been conflated with Jesus and all those who stand against oppression and injustice.

It is this elevation to ‘protector of the innocent’ that has seen a significant amount of fictional work centred around the Ned Kelly story. From Robert Drewe’s Our Sunshine [1991] and Peter Carey’s Booker prize-winning novel True History of the Kelly Gang [2000] to Timothy Bowden’s Undead Kelly [2013] [Figure 3] and Nicole Kelly’s Lament [2020], Ned’s story has not only encompassed lovers and offspring, but also zombies and alternate realities. Hundreds of titles have been published and no doubt many more are planned. It is a story that continues to evolve and mutate with every retelling.

During the First World War, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes series, petitioned the London War Office for ‘Kelly Armour’ to protect the troops. In advocating artificial protection for British soldiers Doyle, who was also a medical doctor, argued that, ‘When Ned Kelly walked unharmed before the Victorian police rifles in his own hand-made armour he was an object-lesson to the world. If an outlaw could do it, why not a soldier?’ [Webb, 2017, p.153]. While the British Army did not officially adopt Doyle’s recommendations, many families, motivated by Doyle’s plea, employed blacksmiths to build protection for their boys. Influenced by tales of bullet-proof men facing off on both sides of the law, or even a battlefield, Ned’s iconic armour and his tale of rebellion has permeated international boundaries to the point where origins are now blurred and sources are confused, or simply dismissed. Gaming, such as Red Dead Online Beta [2019] [Figure 4], offers a classic example of how an industry can copy a copy and be totally unaware of the original. While actual computer games based on Ned Kelly are scant, his imagery, in particular the armour which so fascinated Sidney Nolan and Arthur Conan Doyle can be seen in a myriad of digital incarnations within the best selling worlds of Fallout [2010], Borderlands [2014], Bloodborne [2015], and Battlefield [2016], to name a few.

![Red Dead Online Beta [2019]](https://www.folk2super.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Ned-Dead-Redemption-1024x630.jpg)

Indeed, modern popular culture has reawakened a fascination in the customs and traditions of different societies across the globe. Norse, Greek and Chinese mythology has provided a deep well for creative minds. Reinvented and reimagined, protagonists like Thor, Hercules, and Hua Mulan have been co-opted into contemporary storytelling, filling pages in comics and seats in cinemas. While some children may not be able to pronounce Mjölnir, they can easily identify Thor’s hammer. Whereas these origins remain mostly recognisable, Ned Kelly’s cultural influence, and depth of comprehension, depends largely on locality and circumstance. Here in Ned’s native land the narrative, even those obscured tales, can usually be traced to a perceivable origin, whereas international interpretation is more mystifying. Essentially, the man Ned Kelly is not as famous as the armour.

This thesis intends to illustrate the degree to which the Ned Kelly myth has become a major factor in developing modern day popular culture, in Australia and internationally. From comic book archetypes to gaming antagonists to cinematic superheroes, once we begin to understand the foundations of an origin story it becomes possible to unlock the significant impact the actions of one late 19th century Australian man [and his associates] might have on entertainment, leisure, and learning across the globe. Beginning with an examination of early source materials such as the penny dreadful Ned Kelly: The Ironclad Australian Bushranger [1881], I will chart the significant steps which link modern superhero traits to the past deeds of a man who has become—whether one agrees or disagrees with his actions—a legendary Australian.

Since his execution in 1880, Ned has mythologised into a ‘Robin Hood’ character. He has been accepted into aboriginal narratives, become a political icon, and a figure of Irish-Catholic and working-class resistance to the colonial and, to some degree, contemporary establishment. The proliferation of illustrated newspapers made possible by advances in printing technology and cheap mass publishing in colonial Australian culture, was an aspect of the industrial revolution that focused, nurtured and enabled the popularisation of Ned Kelly as a national symbol.

... from outlaw to national hero in a century, and to international icon in a further twenty years. The still-enigmatic, slightly saturnine and ever-ambivalent bushranger is the undisputed, if not universally admired, national symbol of Australia.

Graham Seal Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History

For this paper to document the extent to which Ned Kelly’s narrative has been manipulated, I will investigate why differing cultures find his story so fascinating. From the story paper Journal des Voyages [1883] to the graphic novel L’histoire de Ned Kelly [2017] the French, by way of illustration, appear attracted to tales of Ned’s insurrection and revolution against his colonial masters. Just as significant, I will explore why Ned’s mythology has, in certain circles, become so convoluted with recitals that bear no actual connection to the source material. Popular culture has reconstructed many aspects of Ned’s folkloric legacy, taking aspects such as the armour and jaxapositioning it in to scenarios alien to its original intention. While these origins have been neglected, as in Kid Colt Outlaw #114 [1964] [Figure 5], it is time to record the heritage and acknowledge the provenance.

The object of this research is to demonstrate the depth of effect Ned Kelly’s folklore has had, and continues to have, on popular culture worldwide. I intend to complete this task by highlighting Ned’s primary areas of influence. This research will connect the paths between creative predisposition and fulfilled propositions by exploring historical artefacts, visual descriptives, figurative language, and expressive documentation surrounding his mythology. The investigation will also shed light on past and current characters and reiterations that have utilised aspects of Ned’s historical and/or imaginative story without a conscious relationship back to the source material borne out of ignorance, apathy, or a misunderstanding of the origins.

Bird, D 1992, Dingo makes us human: Life and land in an Aboriginal Australian culture, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Borlase, J.S. 1881, Ned Kelly: The Ironclad Australian Bushranger, Alfred J Isaacs and Sons, London.

Brown, M 2005, Australian Son: the story of Ned Kelly, Network Creative Services, Greensborough.

Castelli, J.A. 1883, ‘Une Histoire De Bandits En Australie’ in Journal des Voyages #329, Revue des Deux Mondes, Paris.

de Grave, M.E. and, de Grave, J.J. 2017, L’histoire de Ned Kelly, Helium, Paris.

Groth, G 2011, Jack Kirby Interview, viewed 28 October 2020.

Hall, G.W (ed.) 1879, The Book of Keli, Mansfield Guardian, Mansfield.

Jones, I 2002, NED: the exhibition, Network Creative Services, Pimlico.

Kenneally, J.J 1929, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, J. Roy Stevens Printer, Melbourne.

Aveyard, K and, Moran, A and, Vieth, E 2005, Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema, Scarecrow Press, Maryland.

Phillips, J.H. 2003, The North-Eastern Victoria Republic Movement – Myth Or Reality?, viewed 30 October 2020.

Seal, G 2011, Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History, Anthem Press. London.

Shirley, G and, Adams, B 1983, Australian Cinema: the First Eighty Years, Currency Press, Sydney.

Webb, B 2017, Ned Kelly: The Iron Outlaw, New Holland Publishing, Sydney.